| Daisy, gleaming like silver, safe and proud above the hot struggles of the poor. "The great Gatsby" by F. Scott Fitzgerald |

|

Echoes of the Jazz Age --- F. Scott Fitzgerald

It is too soon to write about the Jazz Age with perspective, and without being suspected of premature arteriosclerosis. Many people still succumb to violent retching when they happen upon any of its characteristic words - words which have since yielded in vivedness to the coinages of the underworld. It is as dead as were the Yellow Nineties in 1902. Yet the present writer already looks back to it with nostalgia. It bore him up, flattered him and gave him more money than he had dreamed of, simply for telling people that he felt as they did, that something had to be done with all the nervous energy stored up and unexpended in the War. * * *

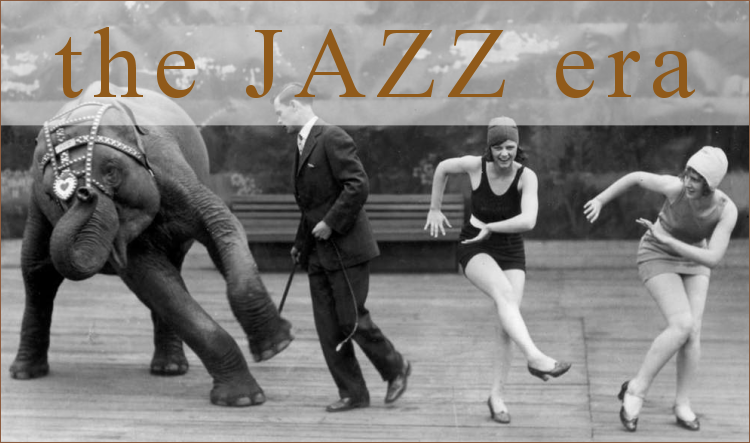

The Jazz Age had had a wild youth and a heady middle age. There was the phase of the necking parties, the Leopold-Loeb murder ( I remember the time my wife was arrested on Queensborough Bridge on the suspicion of being the "Bob-haired Bandit") and the John Held Clothes. In the second phase such phenomena as sex and murder became more mature, if much more conventional. Middle age must be served and pajamas came to the beach to save fat thighs and flabby calves from competition with the one-piece bathing-suit. Finally skirts came down and everything was concealed. Everybody was at scratch now. Let's go - |

|

The phrase "Jazz Age" encompasses a major shift in society, politics and entertainment that took place after the end of World War I in 1918. During these high-flying times, pleasure was the goal, and, for many, money was no object.

Author F. Scott Fitzgerald was the chief chronicler of this time period. Looking back in the 1931 essay Echoes of the Jazz Age, he deemed the era an "age of excess." His legendary novel "The Great Gatsby," which was published in 1925, combines the sense of possibility and the potential tragedy as people redefined the rules that existed before World War I.

In literature, in art, in music, the post-war theme was: abandon tradition, experiment with the unknown, change the rules, dare to be different, innovate, and above all, expose the sham of western civilization, a civilization whose entire system of values was now perceived as one without justification. This was modernism, a reaction against the conventions of liberal, bourgeois, material, decadent western civilization. It's what we might call the avant garde, or bohemian or abstract today. But for the lost generation of post-war Europe, it seemed to be the only way out of either depression or suicide. In a world now proven to be without values, what else was left but what had not yet been tried before?

The Jazz Age was a time of rebellion. Although the 18th amendment banning alcohol in America went into effect in 1920 and lasted throughout the decade, parties did not end, and bootleggers became rich. The liberation wasn't limited to alcohol. Also in 1920, thanks to the 19th amendment, women were able to vote. The Jazz Age also marked a shift in fashion for women, and flapper dresses became all the rage.

Helping to fuel the social change was a sudden rise in wealth and free time. Stock market speculation ran rampant, and people could buy items they had never before dreamed of owning, like cars, radios and records. With technological innovation spreading and more people being able to afford labor-saving devices, they had more time to entertain themselves - especially with jazz music.

The music captured a playful, experimental, innovative spirit that was to guide all entertainment and many lifestyle choices of the time.

Sadly, the Jazz Age landed with a thud along with the stock market in 1929, and the Great Depression replaced all the glamour for which the Jazz Age was so famous.

|

|

| The Jazz |

|

The music the decade was named after, the music that was the soundtrack of the era, that the people danced to. |

|

Paul Whiteman & His Orchestra 1921

Paul Whiteman & His Orchestra 1921

listen to

BECAUSE MY BABY DON'T MEAN MAYBE NOW [1928] by PAUL WHITEMAN & HIS ORCHESTRA

Louis Armstrong

Fletcher Henderson

listen to

HAVE IT READY [1927] by FLETCHER HENDERSON |

As the roaring 1920s wore on, jazz rose in popularity and helped to generate the cultural shift that was taking place. Dances like the Charleston, suddenly became popular among the younger generation thanks to an increase in recordings cut, to the popularity of jazz-inflected pop music such as that of the Paul Whiteman Orchestra and with the beginning of large-scale radio broadcasts in 1922 that enabled Americans to experience different styles of music without physically visiting a jazz club.

The radio provided Americans with a trendy new avenue for exploring the world through broadcasts and concerts from the comfort of their living room. The most popular type of radio show was a "potter palm" - amateur concerts and big-band jazz performances broadcasted from cities like New York and Chicago that became the cultural centers for jazz when musicians moved there. Chicago briefly enjoyed being the capital of jazz, partly because it was home to Jelly Roll Morton, King Oliver, and Louis Armstrong. New York’s scene increased as well. James P. Johnson’s 1921 recording of “Carolina Shout” bridged the gap between ragtime and more advanced jazz styles. In addition, big bands began to pop up throughout the city. Duke Ellington moved to New York in 1923, and four years later became the leader of the house band at the Cotton Club.

The primacy of the soloist was budding thanks to Armstrong’s Hot Five recordings on Okeh Records. Famous songs included “Struttin’ With Some Barbecue,” and “Big Butter and Egg Man.” Saxophonist Sidney Bechet’s virtuosity was documented as well, with his 1923 recording of “Wild Cat Blues” and “Kansas City Blues.”

By featuring virtuosic soloists and performing bombastic blues arrangements, big bands, such as those led by Earl Hines, Fletcher Henderson, and Duke Ellington, began to replace New Orleans jazz in popularity. The concentration of that popularity also began to shift from Chicago to New York, signified by Louis Armstrong’s move there in 1929.

Prohibition in the United States (from 1920 to 1933) banned the sale of alcoholic drinks, resulting in the illicit speakeasies that became the lively venues of the "Jazz Age", when popular music included current dance songs, novelty songs, and show tunes. Jazz started to get a reputation as being immoral and many members of the older generations saw it as threatening the old values in culture and promoting the new decadent values of the Roaring 20s. Professor Henry Van Dyke of Princeton University wrote “...it is not music at all. It’s merely an irritation of the nerves of hearing, a sensual teasing of the strings of physical passion.”

Even the media began to denigrate jazz. The New York Times took stories and altered headlines to pick at Jazz. For instance, that villagers used pots and pans in Siberia to scare off bears, and the newspaper stated that it was Jazz that scared the bears away.

In 1924 Bix Beiderbecke formed The Wolverines and Louis Armstrong joined the Fletcher Henderson dance band as featured soloist for a year, then formed his virtuosic Hot Five band, popularizing scat singing.

Jelly Roll Morton recorded with the New Orleans Rhythm Kings in an early mixed-race collaboration, then in 1926 formed his Red Hot Peppers. There was a larger market for jazzy dance music played by white orchestras, such as Jean Goldkette's orchestra and Paul Whiteman's orchestra. Other influential large ensembles included Fletcher Henderson's band, Duke Ellington's band (which opened an influential residency at the Cotton Club in 1927) in New York, and Earl Hines' Band in Chicago (who opened in The Grand Terrace Cafe there in 1928). All significantly influenced the development of big band-style swing jazz in the following decade. |

|

|

Louis "Satchmo" Armstrong

"The trumpet comes before everything. That's why I married four times - the chicks didn't live with the horn."

To this day, Armstrong is regarded as the father of jazz. With his instantly recognizable deep and distinctive gravelly voice and his sophistication and inventiveness as a trumpet player he changed the course of jazz, as he inspired musicians to improvise using their own unique styles. His influence was pivotal in the first half of the century, and guided the creative output of such figures as Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, and Dizzy Gillespie. The joy he brought to the bandstand as a trumpeter, singer, and bandleader has yet to be matched.

The grandson of slaves, and the son of a prostitute and an absent father, trumpeter Louis Armstrong grew up in the rough streets of New Orleans. He sold newspapers and did other odd jobs to support his mother, but spent most of his time in the red-light district, known as Storyville, where he heard local bands play in bars and brothels.

At age 11, he was arrested for firing a pistol in the street during a New Year’s celebration and was sent to a school for delinquents. This played an important role in the young Armstrong’s musical life, for it was there that he received formal training, and even led the school’s band.

In his teens, Armstrong proved to be a talented cornet player, and soon he was a featured as a soloist in local bands. In 1922, he was invited by bandleader Joe “King” Oliver to join his group in Chicago, Illinois. Armstrong began to outshine Oliver, and ambitiously decided to try his luck in New York City. He moved there briefly in 1924 to join Fletcher Henderson’s big band. During this time he switched from cornet to trumpet.

He returned to Chicago in 1925 to record some of his most famous music with his Hot Five and Hot Seven bands. His playing on these records earned him acclaim and popularity for solos that were virtuosic and joyfully melodic. The risks and liberties he took on the trumpet were were exciting and unprecedented. He also endeared himself to audiences with his warm and often humorous vocals. He is credited with developing the wordless style of improvised singing known as “scat singing“, vocalizing using sounds and syllables instead of actual lyrics.

A highly skilled musician, Armstrong succeeded in balancing his artistic integrity with popular appeal. Renowned for his charismatic stage presence, his personality onstage and off was gregarious and lovable, and he was soon performing all over the country, especially in Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles.

Armstrong was one of the first truly popular African-American entertainers to "cross over," whose skin-color was secondary to his amazing talent in an America that was severely racially divided.

In 1964 the title track from his record “Hello, Dolly!” reached number one on the pop charts, beating even the Beatles. He toured Europe, Africa, and Asia on U.S. State Department-sponsored tours, and continued to thrill audiences until his death in 1971. |

|

|

Paul Whiteman

Paul Samuel Whiteman (March 28, 1890 – December 29, 1967) was an American bandleader and orchestral director.

Leader of the most popular dance bands in the United States during the 1920s, Whiteman's recordings were immensely successful, and press notices often referred to him as the "King of Jazz." Using a large ensemble and exploring many styles of music, Whiteman is perhaps best known for his blending of symphonic music and jazz. His popularity faded in the swing music era of the 1930s, and by the 1940s Whiteman was semi-retired from music.

Whiteman's place in the history of early jazz is somewhat controversial. Detractors suggest that Whiteman's ornately-orchestrated music was jazz in name only (lacking the genre's improvisational and emotional depth), and co-opted the innovations of black musicians. Defenders note that Whiteman's fondness for jazz was genuine (he worked with black musicians as much as was feasible during an era of racial segregation), that his bands included many of the era's most esteemed white jazz musicians, and argue that Whiteman's groups handled jazz admirably as part of a larger repertoire. In his autobiography, Duke Ellington declared, "Paul Whiteman was known as the King of Jazz, and no one as yet has come near carrying that title with more certainty and dignity."

Whiteman was born in Denver, Colorado. After a start as a classical violinist and violist, he led a jazz-influenced dance band, which became popular locally in San Francisco, California in 1918. In 1920 he moved with his band to New York City where they started making recordings for Victor Records which made the Paul Whiteman Orchestra famous nationally.

For more than 30 years Whiteman, referred to as "Pops", sought and encouraged musicians, vocalists, composers, arrangers, and entertainers who looked promising.

Whiteman hired many of the best jazz musicians for his band, including Bix Beiderbecke, Frankie Trumbauer, Joe Venuti, Eddie Lang, Steve Brown, Mike Pingitore, Gussie Mueller, Wilbur Hall (billed by Whiteman as "Willie Hall"), Jack Teagarden, and Bunny Berigan. He also encouraged upcoming African American musical talents, and initially planned on hiring black musicians, but Whiteman's management eventually persuaded him that doing would be career suicide due to racial tension and America's segregation of that time. However, Whiteman crossed racial lines behind-the-scenes, hiring black arrangers like Fletcher Henderson and engaging in mutually-beneficial efforts with recording sessions and scheduling of tours.

In late 1926 Whiteman signed three candidates for his orchestra: Bing Crosby, Al Rinker, and Harry Barris. Whiteman billed the singing trio as The Rhythm Boys. Crosby's prominence in the Rhythm Boys helped launch his career as one of the most successful singers of the 20th century. Paul Robeson (1928) and Billie Holiday (1942) also recorded with the Paul Whiteman Orchestra.

Whiteman signed singer Mildred Bailey in 1929 to appear on his radio program. She first recorded with the Whiteman Orchestra in 1931.

Whiteman had 28 number one records during the 1920s and 32 during his career. At the height of his popularity, eight out of the top ten sheet music sales slots were by the Paul Whiteman Orchestra. | |||

|

|

listen to

CHINA BOY [1929] by PAUL WHITEMAN & HIS ORCHESTRA |

|

|

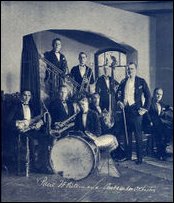

Duke Ellington

" and sometimes I do nothing but take the bow. And I have fun. My thing is having fun."

Growing up in Washington, D.C., the young Edward Kennedy Ellington was dignified and self-confident, earning himself the nickname “Duke".

His father worked as a butler and his mother was the daughter of a slave, and both taught their son the importance of education and hard work. Duke began playing the piano at age seven, but his deep love for music didn’t spark until he was a teenager, after he discovered the ragtime music of pianist James P. Johnson. Soon Duke had a repertoire of original tunes, and he developed a career playing piano in Washington, D.C. clubs.

In 1923, Duke moved to New York City, where the Harlem Renaissance was in full swing, attracting black intellectuals, artists, and musicians to celebrate and explore black culture and creativity. Duke joined the band of another Washington D.C. musician named Elmer Snowden. The band, called “The Washingtonians,” was made up of seven instrumentalists, and they played regularly at the Hollywood Club in Manhattan.

A series of events led to a sudden rise in Duke’s fame.

First, Snowden left the group in 1924. Duke stepped in as bandleader and took on the role of composing for the band. Next, Sidney Bechet, the famed soprano saxophone player from New Orleans joined the ensemble. His virtuosity and gritty New Orleans style brought attention to Duke and his small orchestra. In 1927, after cornet player and bandleader King Oliver declined an offer for a regular gig at Harlem’s Cotton Club, Duke and his band stepped in.

The Cotton Club engagement gave Duke immense exposure, broadcasting performances on the radio and attracting large, mainly white crowds. Soon Duke’s music, which reflected the black experience in Harlem with its bluesy melodies and exotic rhythms, fell into popularity with black and white audiences. At the Cotton Club, Duke’s orchestra had the responsibility of providing music to accompany various performances, including vaudeville, burlesque, and comedy acts.

Ellington liked to describe those who impressed him as "beyond category." These included many of the musicians who were members of his orchestra, some of whom are considered among the best in jazz in their own right, but it was Ellington who melded them into one of the most well-known jazz orchestral units in the history of jazz.

He often composed specifically for the style and skills of these individuals, such as "Jeep's Blues" for Johnny Hodges, "Concerto for Cootie" for Cootie Williams, which later became "Do Nothing Till You Hear from Me" with Bob Russell's lyrics, and "The Mooche" for Tricky Sam Nanton and Bubber Miley. He also recorded songs written by his bandsmen, such as Juan Tizol's "Caravan" and "Perdido" which brought the 'Spanish Tinge' to big-band jazz. Several members of the orchestra remained there for several decades. After 1941, he frequently collaborated with composer-arranger-pianist Billy Strayhorn, whom he called his "writing and arranging companion." Ellington recorded for many American record companies, and appeared in several films.

In 1925 "Duke Ellington and his Kentucky Club Orchestra" grew to a ten-piece organization; they developed their distinct sound by displaying the non-traditional expression of Ellington’s arrangements, the street rhythms of Harlem, and the exotic-sounding trombone growls and wah-wahs, high-squealing trumpets, and sultry saxophone blues licks of the band members. For a short time soprano saxophonist Sidney Bechet played with the group, imparting his propulsive swing and superior musicianship to the young band members. This helped attract the attention of some of the biggest names of jazz, including Paul Whiteman.

Although trumpeter Bubber Miley was a member of the orchestra for only a short period, he had a major influence on Ellington's sound. An early exponent of growl trumpet, his style changed the "sweet" dance band sound of the group to one that was hotter, which contemporaries termed 'jungle' style. He also composed most of "Black and Tan Fantasy" and "Creole Love Call". An alcoholic, Miley had to leave the band before they gained wider fame and he died in 1932 at the age of twenty-nine. He was an important influence on Cootie Williams, who replaced him.

Duke’s popularity grew in the late 1920s. He made several recordings and his music reached audiences across the nation and in Europe.

His reputation increased after his death and the Pulitzer Prize Board bestowed on him a special posthumous honor in 1999. |

|

|

Fletcher Henderson

James Fletcher Hamilton Henderson, Jr. [December 18, 1897 – December 28, 1952] was an American pianist, bandleader, arranger and composer, important in the development of big band jazz and swing music. His was one of the most prolific black orchestras and his influence was vast.

Fletcher Henderson was born in Cuthbert, Georgia. He attended Atlanta University in Atlanta, Georgia and graduated in 1920. After graduation, he moved to New York City to attend Columbia University for a master's degree in chemistry. However, he found his job prospects in chemistry to be very restricted due to his race, and turned to music for a living.

He was recording director for the fledgling Black Swan label from 1921-1923 and in 1922 he formed his own band, which was resident first at the Club Alabam, then at the Roseland, and quickly became known as the best African-American band in New York. For a time his ideas of arrangement were heavily influenced by those of Paul Whiteman, but when Louis Armstrong joined his orchestra in 1924, Henderson realized there could be a much richer potential for jazz band orchestration.

Henderson's band also boasted the formidable arranging talents of Don Redman (from 1922 to 1927) and during the 1920s and very early 1930s, Henderson actually wrote few, if any, arrangements - most of his recordings were arranged by Don Redman (c. 1923-1927) or Benny Carter (after 1927-c. 1931). As an arranger, Henderson came into his own only in the mid-1930s.

His band circa 1925 included Howard Scott, Coleman Hawkins (who started with Henderson in 1923 playing the low tuba parts on bass saxophone and quickly moved to tenor and a leading solo role), Louis Armstrong, Charlie Dixon, Kaiser Marshall, Buster Bailey, Elmer Chambers, Charlie Green, Ralph Escudero and Don Redman.

In 1925, along with fellow composer Henry Troy, he wrote "Gin House Blues", recorded by Bessie Smith and Nina Simone amongst others. He also wrote the very popular jazz composition "Soft Winds".

Although Henderson's music was popular, his band began to fold with the 1929 stock market crash. The loss of financial stability resulted in the selling of many arrangements from his songbooks to the later-to-be-acclaimed "King of Swing" Benny Goodman.

Henderson, along with Don Redman, established the formula for swing music. The two concocted the recipe every swing band played from (i.e. sections 'talking' to one another, 'hot' swing). Swing, its popularity spanning over a decade, was the most fashionable form of jazz ever in the United States.

Henderson was also responsible for bringing Louis Armstrong from Chicago to New York, thus flipping the focal point of jazz in the history of the United States. | |||

|

|

listen to

ONE OF THESE DAYS [1924] by FLETCHER HENDERSON & HIS ORCHESTRA |

|

| The Charleston |

|

The jazz music was perfect for dancing, so people danced like they

never danced before, for when we think of the 20s, we think of the

Charleston, flying beads, knock knees, and crossing hands. |

|

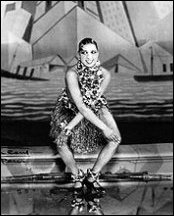

Josephine Baker dancing the Charleston at the Folies Bergère 1926

listen to

I'M GONNA CHARLESTON BACK TO CHARLESTON [1925] played by the MISSOURI JAZZ BAND [LOU GOLD & HIS ORCHESTRA]

|

Flappers wore short dresses and danced the fox trot, the shimmy, the tango,

and the camel-walk. The new music and dances were fast paced and energetic,

like the optimistic 1920's themselves.

People were ready for something new. It came in 1924. It was called the Charleston, the dance that became the dance of the 1920s. A fast dance named for the city of Charleston, South Carolina, that came from a black Broadway show called "Runnin’ Wild", the Ziegfield Follies dancing to the tune "The Charleston" by composer/pianist James P. Johnson.

The Charleston is most frequently associated with white flappers and the

speakeasy. Here, these young women would dance alone or together as a way of

mocking the "drys," or citizens who supported the Prohibition amendment.

Preachers called this jazz and dancing sinful, immoral and provocative, but few young people cared, they were having a good time.

Dancing in the 1920s was always the main entertainment. Parties included dancing

in their evening programs. Churches used dances to attract the young. Schools

taught social dancing to small children. Flappers almost lived for dancing.

The Charleston was an exhibition dance at first, considered too difficult for

any but professionals to master, with its suddenly shifting rhythms and

breathtaking pace. Yet, within a year it had swept the country.

The Charleston is characterized by outward heel kicks combined with an up and

down movement achieved by bending and straightening the knees in time to the

music.

The basic step of the Charleston resembles the natural movement of walking, though it is usually performed in place. The arms swing forward and backwards, with the right arm coming forward as the left leg 'steps' forward, and then moving back as the opposite arm/leg begin their forwards movement. Toes are not pointed, but feet usually form a right angle with the leg at the ankle. Arms are usually extended from the shoulder, either with straight lines, or more frequently with bent elbows and hands at right angles from the wrist (characteristics of many African dances). Styling varies with each Charleston type from this point, though all utilise a 'bounce'.

Dances like the Tango and Charleston received a huge boost in popularity when

featured in movies by stars like Rudolph Valentino and Joan Crawford. Freed from

the restrictions of tight corsets and the large puffed sleeves and long skirts

that characterized dress during the late Victorian era, a new generation of

dancers was swaying, hugging, and grinding to the new rhythms.

In the 1920's and 30's the Lindy hop, named for the pilot Charles Lindburgh's

first solo flight, emerged and was the first dance to include swinging the

partner into the air, as well as jumping in sequence.

People saw the new dances in Hollywood movies and practiced them to phonograph

records or to radio broadcasts before going out on the dance floors of nightclubs

or school gymnasiums.

Magazines and books on social dancing and related social activities were very

popular, as were dance schools teaching all the latest dance crazes. Dance

etiquette inherited from the previous century began to change. Parents who could

afford to would send their children to learn Tap and Ballet dancing. Dance

marathons occurred

every weekend with the longest ever recorded being 3 weeks of dancing.

Dancing began to actively involve the upper body for the first time as women

began shaking their torsos in a dance called the Shimmy. Young people took to

throwing their arms and legs in the air with reckless abandon and hopping or

"toddling" every step in the Foxtrot, and soon every college student was doing

a new dance which became known as the Toddle.

A dance called the "Black Bottom", first introduced in a 1926 Broadway

production, swept not only America, but the entire world within a year.

The overwhelming popularity of the Charleston inspired choreographers and dance

teachers to fabricate and promote several new fad dances to a public hungry for

novelty. A new style of Blues Dancing also developed to fit the disreputable

atmosphere of the speakeasy. |

|

| The Flappers |

|

“I think a woman gets more happiness out of being gay, light-hearted, unconventional,

mistress of her own fate.... I want my daughter to be a flapper, because flappers are brave

and gay and beautiful.” Author Zelda Fitzgerald, 1924. |

|

|

Women were just as anxious as the men to avoid returning to society's rules and roles after the war. Nearly a whole generation of young men had died in the war, leaving nearly a whole generation of young women without possible suitors. Young women decided that they were not willing to waste away their young lives waiting idly for spinsterhood; they were going to enjoy life.

They found themselves expected to settle down into the humdrum routine of American life as if nothing had happened, to accept the moral dicta of elders who seemed still to be living in a Pollyanna land of rosy ideals which the war had killed for them. They couldn't do it, and they very disrespectfully said so. In William and Mary Morris' Dictionary of Word and Phrase Origins, they state, "In America, a flapper has always been a giddy, attractive and slightly unconventional young thing who, in [H. L.] Mencken's words, 'was a somewhat foolish girl, full of wild surmises and inclined to revolt against the precepts and admonitions of her elders.'" In his lecture in 1920, on Britain's surplus of young women caused by the loss of young men in war, Dr. R. Murray-Leslie criticized "the social butterfly type… the frivolous, scantily-clad, jazzing flapper, irresponsible and undisciplined, to whom a dance, a new hat, or a man with a car, were of more importance than the fate of nations."

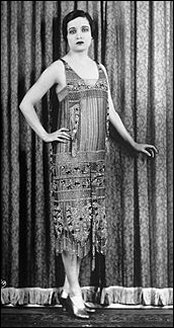

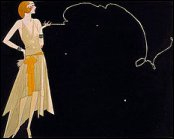

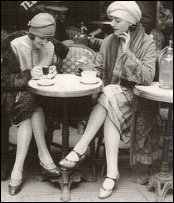

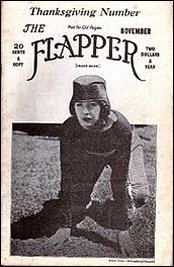

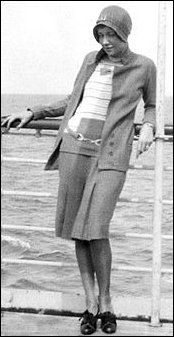

Flapper in the 1920s was a term applied to a "new breed" of young Western women who wore short dresses, bobbed their hair, listened to jazz, danced the Charleston and flaunted their disdain for what was then considered acceptable behavior. Flappers were seen as brash for wearing excessive makeup, drinking, treating sex in a casual manner, smoking, driving automobiles and otherwise flouting social and sexual norms.

Flappers had their origins in the period of Liberalism, social and political turbulence and increased transatlantic cultural exchange that followed the end of the First World War, as well as the export of American jazz culture to Europe, and these rebellious young women of the Jazz age were nothing like their predecessors.

The first appearance of the word and image in the United States came from the popular 1920 Frances Marion film, "The Flapper", starring Olive Thomas. Other actresses, such as Clara Bow, Louise Brooks, Colleen Moore and Joan Crawford would soon build their careers on the same image, achieving great popularity.

Writers in the United States such as F. Scott Fitzgerald and Anita Loos and illustrators such as Russell Patterson, John Held, Jr., Ethel Hays and Faith Burrows popularized the flapper look and lifestyle through their work, and flappers came to be seen as attractive, reckless, and independent. Among those who criticized the flapper craze was a Harvard psychologist who said that flappers had "the lowest degree of intelligence" and constituted "a hopeless problem for educators."

Flappers' behavior was considered outlandish at the time and redefined women's roles. The

image of flappers were young women who went by night to jazz clubs where they danced

provocatively, smoked cigarettes through long holders, and dated freely, perhaps

indiscriminately. They rode bicycles, drove cars, and openly drank alcohol, a defiant act in

the American period of Prohibition. Petting Parties, where petting ("making out" or foreplay)

was the main attraction, became popular.

Flappers began working outside the home and challenging women's traditional societal roles. They advocated voting and women's rights and they were considered a significant challenge to traditional Victorian gender roles, devotion to plain-living and hard work, religion and more. Increasingly, women discarded old, rigid ideas about roles and embraced consumerism and personal choice.

For all the concern about women stepping out of their traditional roles, however, some say

many flappers weren't necessarily particularly engaged in politics. In fact, older

suffragettes, who fought for the right for women to vote, viewed flappers as vapid and in some

ways unworthy of the enfranchisement they had worked so hard to win.

Others argued, though, that flappers' laissez-faire attitude was simply a natural progression of feminine liberation, the rights having already been won. Dorothy Dunbar Bromley, a noted liberal writer at the time, summed up this dichotomy by describing flappers as "truly modern", "New Style" feminists who "admit that a full life calls for marriage and children" and also "are moved by an inescapable inner compulsion to be individuals in their own right."

Flappers had their own slang, using terms like "snuggle pup" (a man who frequents petting parties) and "barney-mugging" (sex).

Their dialect sometimes reflected their feelings about marriage and drinking habits: "I have to see a man about a dog" often meant going to buy whiskey, and a "handcuff" or "manacle" was an engagement or wedding ring. Also reflective of their preoccupations were phrases to express approval, such as "That's so Jake", "That's the bee's knees," and the popular "the cat's meow" or "cat's pyjamas". A 1922 U.S. newspaper article lists the words "junk", "necker", "heavy necker" and "necking parties" as contemporary flapper slang.

In addition to their irreverent behavior, flappers were known for their style, which largely

emerged as a result of French fashions, especially those pioneered by Coco Chanel and the effect

on dress of the rapid spread of American jazz and the popularization of dancing that

accompanied it. Called garçonne in French ("boy" with a feminine suffix), flapper style made

girls look young and boyish and the short hair, flattened breasts, and straight waists

accentuated it.

To look more like a boy, women tightly wound their chest with strips of cloth in order to flatten it. She wore stockings - made of rayon ("artificial silk") starting in 1923 - which the flapper often wore rolled over a garter belt.

Flapper dresses were straight and tight, leaving the arms bare (sometimes no straps at all) and dropping the waistline to the hips, the colours were lighter and brighter and they were often embroidered or decorated with beads and tassels. Fashionable colours mentioned in an advertisement for frocks, included "Roseda, Orchid, Bracken, Amethyst and Navy".

Skirts rose to just below the knee by 1927, allowing flashes of leg to be seen when a girl danced or walked through a breeze, although the way they danced made any long loose skirt flap up to show their legs. To complement the newly revealed legs, sexy stockings became a daring flesh colour instead of the traditional black and high heels came into vogue.

Flappers did away with corsets and pantaloons in favor of "step-in" panties. Without the old restrictive corsets, flappers wore simple bust bodices to make their chest hold still when dancing. They also wore new, softer and suppler corsets that reached to their hips, smoothing the whole frame, giving women a straight up and down appearance, as opposed to the old corsets which slenderized the waist and accented the hips and bust.

The lack of curves of a corset promoted the boyish look and to create this look, the Symington Side Lacer was invented and became a popular essential as an every-day bra. This type of bra was made to pull in the back to flatten the chest and large breasts were commonly regarded as a trait of unsophistication. Hence, flat chests became appealing to women.

Boyish haircuts were in vogue, especially the Bob cut, Eton crop, where the hair was given a virtual short back and sides and Shingle bob, where the hair was cut shorter at the back. Finger waves were achieved by Marcel Waves (perms), but for those who could not afford it, rags left in the hair overnight were the only alternative.

Hats were still required wear and popular styles included the Newsboy cap and the head-hugging Cloche hat, often pulled way down over the ears and eyes.

Jewelry usually consisted of art deco pieces, especially dangling earrings and long necklaces or many layers of beaded necklaces. Pins, rings, and brooches came into style. Horn-rimmed glasses were also popular.

The evolving flapper look required 'heavy makeup' in comparison to what had previously been

acceptable outside of professional usage in the theatre. Flappers tended to wear 'kiss proof'

lipstick and with the invention of the metal lipstick container as well as compact mirrors, bee

stung lips came into vogue.

Dark eyes, especially Kohl-rimmed, were the style and blush came into vogue now that it was no longer a messy application process, as well as pale blue eye shadow in the evening and plucked eyebrows. Originally, pale skin was considered most attractive. However, tanned skin became increasingly popular when Coco Chanel donned a tan after spending too much time in the sun on holiday – it suggested a life of leisure, without the onerous need to work. Women wanted to look fit, sporty, and, above all, healthy.

Liberated from restrictive dress, from laces that interfered with breathing, and from hoops

that needed managing, suggested liberation of another sort. The new found freedom to breathe

and walk, encouraged movement out of the house, and the flapper took full advantage. The

flapper was an extreme manifestation of changes in the lifestyles of American women made

visible through dress.

The short

skirt and bobbed hair were likely to be used as a symbol of emancipation. Signs of the moral

revolution consisted of: premarital sex, birth control, drinking, and contempt for older

values. Before the war, a lady did not set foot in a saloon; after the war she entered a

speakeasy as thoughtlessly as she would go into a railroad station. Women had taken to

swearing and smoking, using contraceptives and raising their skirts above the knee and rolling

her hose below it. Women were now competing with men in the business world and obtaining

financial independence and, therefore, other kinds of independence from men.

The New Woman was pushing the boundaries of gender identity, representing sexual and economic freedom. She cut her hair short and took to loose-fitting clothing and low cut dresses. No longer restrained by a tight waist and long trailing skirts and the need for a man’s help at every turn, the modern woman of the 1920s was an independent thinker, who no longer followed the ordinances of those before her.

The flapper epitomized the prevailing conceptions of women and her role during the Roaring 20s. The flappers' ideal was motion with characteristics being intensity, energy, and volatility. She refused the traditional moral code. Modesty, chastity, morality, and traditional concepts of male and female were seemingly becoming invisible.

The male equivalent of the flapper was the 'sheik', young men with ukeleles, racoon coats and bell-bottom trousers.

|

Actress Alice Joyce, 1926

"Where there's smoke, there's fire"

by Russell Patterson

Actress Norma Talmadge

Clara Bow, 1921

Billy Dove on the cover of Flapper magazine, 1922

|

|

|

Coco Chanel

"Fashion is not something that exists in dresses only. Fashion is in the sky, in the street,

fashion has to do with ideas, the way we live, what is happening."

Gabrielle Bonheur Chanel [19 August 1883 – 10 January 1971] whose modernist philosophy, menswear-inspired fashions, and pursuit of expensive simplicity made her an important figure in 20th-century fashion. Her extraordinary influence on fashion was such that she was the only person in the couturier field to be named on Time 100: The Most Important People of the Century.

Gabrielle Chanel was born in Saumur, France. In 1895, when she was 12 years old, her mother died of tuberculosis and her father left the family, resulting in Gabrielle spending six years in the orphanage of the Roman Catholic monastery of Aubazine, where she learned the trade of a seamstress. School vacations were spent with relatives in the provincial capital, where female relatives taught Coco to sew with more flourish than the nuns at the monastery were able to demonstrate.

When Gabrielle turned eighteen, she was obliged to leave the orphanage and was affiliated with the circus of Moulins as a cabaret singer. During this time, she performed in bars in Vichy and Moulins where she was called "Coco." Some say that the name comes from one of the songs she used to sing, and Coco herself said that it was a "shortened version of coquette, the French word for 'kept women'".

While she failed to get steady work as a singer, it was at Moulins that she met the rich young textile heir, Étienne Balsan. She became his mistress but kept her day job in a tailoring shop. Balsan lavished on her the beauties of the rich life: diamonds, dresses, and pearls.

While living with Balsan, Coco began designing hats as a hobby, which soon became a deeper interest of hers. "After opening her eyes", as she would say, Coco left Balsan and took over his apartment in Paris.

In 1909 Coco met and began an affair with one of Balsan's friends, Captain Arthur Edward 'Boy' Capel. Boy financed Coco's first shops and his own clothing style, notably his jersey blazers, inspired her creation of the Chanel look.

The affair lasted nine years, even after Boy married an aristocratic English beauty in 1918. His death in a car accident, in late 1919, was the single most devastating event in Chanel's life. Coco erected a roadside memorial at the site of the accident and visited it in later years to place flowers there.

Coco became a licensed modiste (hat maker) in 1910 and opened a boutique at 21 rue Cambon,

Paris, named Chanel Modes. In 1913, she established a boutique in Deauville, where she introduced luxe casual clothes

that were suitable for leisure and sport.

Coco launched her career as fashion designer when she opened her next boutique, titled Chanel-Biarritz, in 1915, catering to the wealthy Spanish clientele who holidayed in Biarritz and were less affected by the war. Coco created loose casual clothes made out of jersey, a material typically used for men's underwear. By 1919, Chanel was registered as a couturiere and established her maison de couture at 31 rue Cambon.

Coco Chanel revolutionized haute couture fashion by replacing the traditional corseted silhouette with the comfort of simple suits and long, slender dresses. And by 1920 the silhouette of her clothing designs have come to be the epitome of 20's style.

Chanel's frequently incorporated ideas from male fashion into her designs and her simpler lines of women's couture led to the popular "flat-chested" look of the 1920s, the styles we associate with flappers. She worked in neutral tones of beige, sand, cream, navy and black, in soft fluid jersey fabrics cut with simple shapes that did not require corsetry or waist definition. They were clothes made for comfort and ease in wear, making them revolutionary and modern.

Her relaxed and unstructured clothing changed the way women dressed for outdoor activities, liberating women. Her jersey dresses, often in navy and gray, were cut to flatter the figure rather than to emphasize and distort the natural body shape.

Coco Chanel's vision was to replace opulent, 'sexy' pieces with items which conveyed casual elegance. Today, Chanel is most famous for the "little black dress".

|

|

| The Lost Generation |

|

The new generation of Americans was “dedicated more than the last to the fear of poverty and

the worship of success; grown up to find all Gods dead, all wars fought, all faiths in man

shaken.” F. Scott Fitzgerald, in his first novel, 'This Side of Paradise'

|

|

Gertrude Stein

|

The 1920s was the first decade to emphasize youth culture and the term "the lost generation" was coined by Gertrude Stein who used it to describe the young people of the 1920's who rejected American post World War I values.

The "Lost Generation" defines a sense of moral loss or aimlessness apparent in literary figures during the 1920s. World War I seemed to have destroyed the idea that if you acted virtuously, good things would happen. Many good, young men went to war and died, or returned home either physically or mentally wounded (for most, both), and their faith in the moral guideposts that had earlier given them hope, were no longer valid...they were "Lost."

The American writers of the Lost Generation rebelled against what America had become by the 1900’s. At this point in time, America had become a great place to go into some area of business but seemed devoid of a cosmopolitan culture. The writers of the Lost Generation's solution to this issue was to pack up their bags and travel to Europe’s cosmopolitan cultures, such as Paris and London. Here they expected to find literary freedom and a cosmopolitan way of life.

These writers were instrumental in changing America's style of writing from Victorian to modern.

The three best known writers among The Lost Generation are F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway and John Dos Passos. Others are: James Joyce, D. H. Lawrence , T. S. Eliot , Thomas Mann, Marcel Proust , Ezra Pound, Sherwood Anderson, Kay Boyle, Hart Crane, Ford Maddox Ford and Zelda Fitzgerald.

Ernest Hemingway, perhaps the leading literary figure of the decade, took Stein's phrase, and used it as an epigraph for his first novel, 'The Sun Also Rises'. Because of this novel's popularity, The Lost Generation is the enduring term that has stayed associated with writers of the 1920's.

The literary figures of the Lost Generation criticized American culture in creative fictional stories which had the themes of self-exile, indulgence, care-free living and spiritual alienation.

For example, Fitzgerald's 'This Side of Paradise shows' the young generation of the 1920's masking their general depression behind the forced exuberance of the Jazz Age. Another of Fitzgerald's novels, 'The Great Gatsby' does the same, where the illusion of happiness hides a sad loneliness for the main characters.

Hemingway's novels pioneered a new style of writing which many generations after tried to

imitate. Hemingway did away with the florid prose of the 19th century Victorian era and

replaced it with a lean, clear prose based on action. He also employed a technique by which he

left out essential information of the story in the belief that omission can sometimes

strengthen the plot of the novel. The novels produced by the writers of the Lost Generation give insight into the lifestyles that people lead during the 1920's in America, and the literary works of these writers were innovative for their time and have influenced the writing of many future generations |

|

|

The Great Gatsby

"They were careless people, Tom and Daisy - they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made..."

Another of the many names for the 1920's is the Gatsby era, after the famous novel by F. Scott

Fitzgerald, 'The Great Gatsby' that epitomizes and describes the zeitgeist of the time.

Written in 1925, 'The Great Gatsby' was symbolic and manifest all the pre-crash hubris and prosperity that engulfed America at the time. It was F. Scott Fitzgerald's third book and this novel of the Jazz Age stands as the supreme achievement of his career that has been acclaimed by generations of readers.

'The Great Gatsby' takes place from spring to autumn of 1922, telling the story of the fabulously wealthy Jay Gatsby and his love for the beautiful Daisy Buchanan. Of lavish parties on Long Island's North Shore at a time when The New York Times noted that "gin was the national drink and sex the national obsession". It is an exquisitely crafted tale of America in the 1920s, written by a man influenced by the romance of the era, but a man who could see the evils of the choices being made and is one of the great classics of twentieth-century literature, a paragon of the Great American Novel. The Modern Library named it the second best novel of the 20th Century.

After the birth of their child, Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald moved to Great Neck, Long Island in October 1922, appropriating Great Neck as the setting for The Great Gatsby. Progress on the novel was slow. In May 1923, the Fitzgeralds moved to the French Riviera, in true Lost Generation fashion, where the novel was finished.

THE STORY

Nick Carraway, having graduated from Yale and fought in World War I, has returned home to begin a career. He is restless and decided to move to New York to learn the bond business. Nick rented a house in Long Island and became Jay Gatsby's neighbour and the narrator of his story. Rumors run rampant about Gatsby's accumulation of wealth and his lavish soirees.

Tom and Daisy Buchanan live across the bay in the more fashionable East Egg. Daisy is Nick's cousin and Tom had been in the same senior society at Yale. They invite Nick to dinner at their mansion where he meets a young woman named Jordan Baker, a friend of Daisy's whom she wants Nick to date. Daisy now has a young child, although she has remained beautiful and charming. Tom is muscular, brusque and fancies himself an intellectual. During dinner the phone rings, and when Tom and Daisy leave the room, Jordan informs Nick that the caller is Tom's mistress from New York.

Myrtle Wilson, Tom's mistress, lives in a section of Long Island known as the Valley of Ashes, where Myrtle's husband, George Wilson, owns a garage. Painted on a large billboard nearby is a fading advertisement for an ophthalmologist: a set of huge eyes looking through a pair of glasses.

About three weeks after the soirée at the Buchanans', Tom takes Nick to meet the Wilsons. He then takes Nick and Myrtle to New York to a party in a flat he is renting for her. The party breaks up when Myrtle insolently starts shouting Daisy's name, and Tom breaks her nose with a blow of his open hand.

Several weeks later Nick is invited to one of Gatsby's elaborate parties. He attends with Jordan and finds that many of the guests are uninvited and know very little about their host, leading to much speculation about his past. Nick meets Gatsby and notices that he does not drink or join in the revelry of the party.

On the way to lunch in New York with Nick, Gatsby tells Nick that he is the son of a rich family ("all dead now") from San Francisco and that he attended Oxford. During lunch Gatsby introduces Nick to his business associate, Meyer Wolfsheim, who fixed the World Series in 1919. Nick is astonished and slightly unsettled.

At tea that afternoon Nick finds out that Gatsby wants Nick to arrange a meeting between him and Daisy. Gatsby and Daisy had loved each other five years ago, but he was penniless and chose to let Daisy believe that he was as well off as she was. Gatsby was then sent overseas by the army. Daisy had given up waiting for him and had married Tom. After the War, Gatsby decided to win Daisy back by buying a house in West Egg and throwing lavish parties in the hopes that she would attend. His house is directly across the bay from hers, and he can see the green light at the end of Daisy's dock.

Gatsby and Daisy meet for the first time in five years, and he tries to impress her with his mansion and his wealth. Daisy is overcome with emotion and their relationship begins anew. She and Tom finally attend one of Gatsby's parties, but she dislikes it. Gatsby remarks unhappily that their relationship is not like how it was five years ago.

Tom, Daisy, Gatsby, Nick and Jordan get together at Daisy's house, where they meet Daisy's young daughter. They decide to go to the city to escape the heat. Tom, Jordan and Nick take Gatsby's car, a yellow Rolls-Royce. Daisy and Gatsby go in Tom's car, a blue coupé. On the way to the city, Tom stops at Wilson's garage to fill up the tank. Wilson is distraught and ill, saying his wife has been having an affair, though he doesn't know with whom. Tom feels Myrtle watching them from the window.

The party goes to a hotel suite, where Tom confronts Gatsby about his relationship with Daisy. Gatsby demands that Daisy leave Tom and tell him that she never loved him. Daisy is unwilling to do either, admitting that she did love Tom once, which shocks Gatsby. Tom accuses Gatsby of bootlegging and other illegal activities, and Daisy begs to go home. Gatsby and Daisy drive back together in Gatsby's car, followed by the rest of the party in Tom's car. On the way home by Wilson's garage, Myrtle runs out into the street, believing it to be Tom coming by in his car, and the yellow Rolls-Royce hits and kills her before speeding off. Gatsby tells Daisy, who was driving, that he'll take the blame. When Tom arrives at Wilson's garage shortly afterward, he is horrified to find Myrtle dead. He believes Gatsby killed her and drives home in tears.

Once home, Tom and Daisy seem to have reconciled. After a sleepless night, Nick goes over to Gatsby's house where Gatsby ponders the uncertainty of his future with Daisy.

Wilson has been restless from grief, convinced that Myrtle's death was not accidental. He goes around town inquiring about the yellow Rolls-Royce. While Gatsby is relaxing in his pool, Wilson shoots and kills him before killing himself.

Nick struggles to arrange Gatsby's funeral, finding that while he was well-connected in life, very few people, especially business associates like Wolfsheim, are willing to attend his funeral. Daisy is unable to be reached after going off on vacation with Tom. In the end, only Nick, a few servants, and Gatsby's father, Mr. Gatz, are present. Mr. Gatz proudly tells Nick about his son, who was born James Gatz and worked tirelessly to improve and reinvent himself. Jay Gatsby died with but one friend to remember him. Nick decides to move back West, breaking things off with Jordan Baker. After Tom reveals that he told Wilson that the yellow car was Gatsby's, Nick loses respect for the Buchanans and shakes Tom's hand one last time before going on his own way. |

|

|

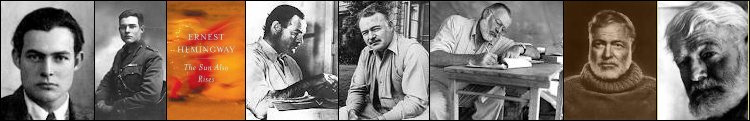

Ernest Hemingway

“I was always embarrassed by the words sacred, glorious, and sacrifice and the expression in

vain. We had heard them... and had read them... now for a long time and I had seen nothing

sacred, and the things that were glorious had no glory and the sacrifices were like the

stockyards of Chicago if nothing was done with the meat except to bury it.”

from 'A Farewell to Arms'

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961), one of the most celebrated refugee authors of his time, wrote his first works during the Jazz era.

His distinctive writing style, characterized by economy and understatement, influenced 20th-century fiction, as did his life of adventure and his public image. He won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1954 and many of his works are classics of American literature.

Hemingway was born and raised in the conservative community of Oak Park, Illinois. The family owned a summer home on Walloon Lake, Michigan, where Hemingway learned to hunt, fish and camp in the woods and lakes of Northern Michigan. These early experiences in nature instilled a passion in him for outdoor adventure and living in remote or isolated areas.

Rebelling against his well-educated parents' attempts to send him to college, he worked for a few months as a cub reporter for The Kansas City Star after leaving high school. His idea of education did not consist of lectures and research papers, but of life experiences and his love of reading. Hemingway's readings centered around Russian writers such as Tolstoy and Turgenev and Tolstoy was a primary influence in Hemingway's writings.

He then left for the Italian front where his experiences as an ambulance driver in World War I had a profound impact on him and became the basis for his novel 'A Farewell to Arms'.

Hemingway was a journalist before becoming a novelist and he relied on the Star's style guide as a foundation for his writing: "Use short sentences. Use short first paragraphs. Use vigorous English. Be positive, not negative." Hemingway used this journalistic writing style in his creative work as well, narrating with observation and description, rather than rhetoric views, "in which meaning is established through dialogue, through action, and silences — a fiction in which nothing crucial, or at least very little, is stated explicitly."

Hemingway referred to his style as the iceberg theory: in his writing the facts float above water, the supporting structure and symbolism operate out-of-sight. Writing in 'The Art of the Short Story', he explains: "A few things I have found to be true. If you leave out important things or events that you know about, the story is strengthened. If you leave or skip something because you do not know it, the story will be worthless. The test of any story is how very good the stuff that you omit."

The concept of war fascinated Hemingway, as well as the experiences one could endure in a lifetime. 'A Farewell to Arms' depicted the uselessness for words such as honor and glory, because they were not the first things in a soldier's mind as he walked onto the battlefield and in his novels.

In 1918, he was seriously wounded and returned home within the year. Despite his wounds, Hemingway carried an Italian soldier to safety, for which he received the Italian Silver Medal of Bravery. Still only eighteen, Hemingway said of the incident: "When you go to war as a boy you have a great illusion of immortality. Other people get killed; not you ... Then when you are badly wounded the first time you lose that illusion and you know it can happen to you."

In 1922 Hemingway married Hadley Richardson, the first of his four wives, and the couple moved to Paris, where he worked as a foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star, arriving with a young wife and the ambition to be a great writer.

Hemingway told a friend, "If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man, then wherever you go for the rest of your life, it stays with you, for Paris is a moveable feast." His 'A Moveable Feast' is a marvelous book that gives a glimpse of what Paris was like in the 1920's. For Ernest Hemingway, Paris was just that, a movable feast that he took with him everywhere he went. Like many other writers and artists, Paris became his adopted home.

He had a letter of introduction to Gertrude Stein, who became Hemingway's mentor for a period, introducing him to the expatriate artists and writers of the Montparnasse Quarter, the modernist writers and artists of the "Lost Generation". A regular at Stein's salon, Hemingway met influential painters such as Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró and Juan Gris. However, Hemingway eventually withdrew from Stein's influence and their relationship deteriorated into a literary quarrel that spanned decades.

Hemingway met Ezra Pound by chance and they forged a strong friendship. Pound, older by fourteen years, recognized and fostered the young talent he found in Hemingway. And he introduced Hemingway to the Irish writer James Joyce, with whom Hemingway frequently embarked on alcoholic sprees.

Of course Hemingway was strongly influenced by these modernist writers and artists of the 1920s, and his first novel, 'The Sun Also Rises', published in 1926, was about Paris. The New York Times wrote of Hemingway's first novel: "No amount of analysis can convey the quality of 'The Sun Also Rises'. It is a truly gripping story, told in a lean, hard, athletic narrative prose that puts more literary English to shame."

After a brief sojourn to Toronto where their son was born in 1923, the Hemingways returned to Paris in 1924 and moved into a new apartment on the Rue Notre Dame des Champs. Hemingway helped Ford Maddox Ford edit the transatlantic review in which were published works by Pound, John Dos Passos, and Gertrude Stein as well as some of Hemingway's own early stories such as 'Indian Camp', which received considerable praise. Ford saw it as an important early story by a young writer, and critics in the United States claimed Hemingway reinvigorated the short story with his use of declarative sentences and his crisp style. Six months earlier, Hemingway met F. Scott Fitzgerald, and the pair formed a friendship of "admiration and hostility".

Fitzgerald's 'The Great Gatsby' had been published that year, Hemingway read it, liked it, and decided his next work had to be a novel.

Since his first visit to see the bullfighting at the Festival of San Fermín in Pamplona in 1923, Hemingway was fascinated by the sport. He saw in it the brutality of war juxtaposed against a cruel beauty. In June 1925, Hemingway and Hadley left Paris for their annual visit to Pamplona, accompanied by a group of American and British expatriates. The trip inspired Hemingway's first novel, 'The Sun Also Rises', which he began to write immediately after the fiesta, finishing in September. The novel presents the culture of bullfighting with the concept of afición, depicted as an authentic way of life, contrasted with the Parisian bohemians, depicted as inauthentic. Hemingway believed bullfighting was "of great tragic interest, being literally of life and death."

'The Sun Also Rises' epitomized the post-war expatriate generation and received good reviews. Hemingway himself later wrote to his editor Max Perkins that the "point of the book" was not so much about a generation being lost, but that "the earth abideth forever".

After divorcing Hadley Richardson in 1927 Hemingway married Pauline Pfeiffer. By the end of the year Pauline, who was pregnant, wanted to move back to America. John Dos Passos recommended Key West, they left Paris in March 1928 and Hemingway "never again lived in a big city". He wrote of Key West in 1933, "We have a fine house here, and kids are all well,". 'A Farewell to Arms' was published on 27 September 1928.

During the early 1930s Hemingway spent his winters in Key West and summers in Wyoming, where he found "the most beautiful country he had seen in the American West" and hunting that included deer, elk, and grizzly bear. In 1933 Hemingway and Pauline went on a ten week safari to East Africa and on his return to Key West in early 1934 Hemingway began work on 'Green Hills of Africa', published in 1935 to mixed reviews. Hemingway bought a boat in 1934, named it the Pilar, and began sailing the Caribbean.

In 1937 Hemingway agreed to report on the Spanish Civil War for the North American Newspaper Alliance

In the spring of 1939, Hemingway, back from Spain, crossed to Cuba in his boat to live in the Hotel Ambos Mundos in Havana. This was the separation phase of a slow and painful split from Pauline, which had begun when Hemingway met war correspondent Martha Gellhorn, before leaving for Spain.

He divorced Pauline in 1940 and married Martha, who inspired him to write his most famous novel, 'For Whom the Bell Tolls'. It sold half a million copies within months and was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. He moved his primary summer residence to Ketchum, Idaho and his winter residence to Cuba.

They split when he met Mary Welsh in London during World War II and he married her in 1946. During this war he was present at D-Day and the liberation of Paris. Hemingway and Mary had a series of accidents and health problems after the war and he became depressed as his literary friends died: in 1939 Yeats and Ford Maddox Ford, in 1940 Scott Fitzgerald, in 1941 Sherwood Anderson and James Joyce, in 1946 Gertrude Stein and the following year in 1947, Max Perkins.

In 1948 Hemingway and Mary traveled to Europe and in Venice he fell in love with the then 19 year old Adriana Ivancich. The platonic love affair inspired the novel 'Across the River and Into the Trees', published in 1950 to bad reviews. The relationship with Adriana lasted until 1955. In 1951 Hemingway wrote the draft of 'Old Man and the Sea' in eight weeks, considering it "the best I can write ever for all of my life". 'The Old Man and the Sea' became a book-of-the month selection, made Hemingway an international celebrity, and won the Pulitzer Prize in May 1952, a month before he left for his second trip to Africa. Here he was almost killed in a plane crash that left him in pain and ill-health for much of the rest of his life. Hemingway, who had been "a thinly controlled alcoholic throughout much of his life, drank more heavily than usual to combat the pain of his injuries."

1954 Hemingway received the Nobel Prize in Literature, for "his mastery of the art of narrative, most recently demonstrated in The Old Man and the Sea, and for the influence that he has exerted on contemporary style."

Because he was suffering pain from the African accidents, he decided against traveling to Stockholm. Instead he sent a speech to be read, defining the writer's life: "Writing, at its best, is a lonely life. Organizations for writers palliate the writer's loneliness but I doubt if they improve his writing. He grows in public stature as he sheds his loneliness and often his work deteriorates. For he does his work alone and if he is a good enough writer he must face eternity, or the lack of it, each day."

From the end of the year in 1955 to early 1956, Hemingway was bedridden. He was told to stop drinking to mitigate liver damage, advice he initially followed but then disregarded.

In October 1956, during a trip to Europe he became sick again, and was treated for "high blood pressure, liver disease, and arteriosclerosis".

In November, while in Paris, he was reminded of trunks he had stored in the Ritz Hotel in 1928 and never retrieved. The trunks were filled with notebooks and writing from his Paris years. Excited about the discovery, when he returned to Cuba in 1957 he began to shape the recovered work into his memoir 'A Moveable Feast'. By 1959 he ended a period of intense activity: he finished 'A Moveable Feast', brought 'True at First Light' to 200,000 words; added chapters to 'The Garden of Eden' and worked on 'Islands in the Stream'. The latter three were stored in a safe deposit box in Havana, as he focused on the finishing touches for 'A Moveable Feast'.

In 1959 he bought a home overlooking the Big Wood River, outside of Ketchum, and left Cuba, leaving art and manuscripts in a bank vault in Havana. After the 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion, his Cuban house was expropriated by the Cuban government, complete with Hemingway's collection of "four to six thousand books".

Hemingway committed suicide in the summer of 1961 after his health declined further, his eyesight started failing and he was treated for a series of mental illnesses.

Medical records made available in 1991 confirm that Hemingway had hemochromatosis, a genetic disease in which the inability to metabolize iron culminates in mental and physical deterioration. Added to Hemingway's physical ailments was the additional problem that he had been a heavy drinker for most of his life.

The simplicity of Hemingway's prose is deceptive. Zoe Trodd believes Hemingway crafted skeletal sentences in response to Henry James's observation that World War I had "used up words." Hemingway offers a "multi-focal" photographic reality. The syntax, which lacks subordinating conjunctions, creates static sentences. The photographic "snapshot" style creates a collage of images. Many types of internal punctuation are omitted in favor of short declarative sentences. The sentences build on each other, as events build to create a sense of the whole. Multiple strands exist in one story, an "embedded text" bridges to a different angle. He also uses other cinematic techniques of "cutting" quickly from one scene to the next, or of "splicing" a scene into another. Intentional omissions allow the reader to fill the gap, as though responding to instructions from the author, and create three-dimensional prose.

In the late summer that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels. Troops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the trees.

The opening passage of 'A Farewell to Arms' shows Hemingway's use of the word 'and'.

In his literature, and in his personal writing, Hemingway habitually used the word "and" in place of commas. This may serve to convey immediacy. Hemingway's polysyndetonic sentence uses conjunctions to juxtapose startling visions and images, Jackson Benson compares them to haikus. Many of Hemingway's followers misinterpreted his lead and frowned upon all expression of emotion. Saul Bellow satirized this style as "Do you have emotions? Strangle them." However, Hemingway's intent was not to eliminate emotion, but to portray it more scientifically. Hemingway thought it would be easy, and pointless, to describe emotions, he sculpted collages of images in order to grasp "the real thing, the sequence of motion and fact which made the emotion and which would be as valid in a year or in ten years or, with luck and if you stated it purely enough, always."

Hemingway's legacy to American literature is his style: writers who came after him emulated it or avoided it. After his reputation was established with the publication of 'The Sun Also Rises', he became the spokesperson for the post–World War I generation, his books were burned in Berlin in 1933, "as being a monument of modern decadence", and disavowed by his parents as "filth".

From the time he had gotten down off the train and the baggage man had thrown his pack out of the open car door things had been different. Seney was burned, he knew that. He hiked along the road, sweating in the sun, climbing to cross the range of hills that separated the railway from the pure plains.

From 'Big Two Hearted River'

|

|

| Art Deco |

|

Sunbursts, chryselephantine, ziggurats, streamlining, dinanderie, black & amber. The way the world looked. |

|

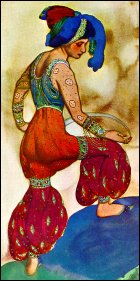

Costume from the Ballets Russes

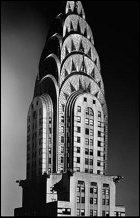

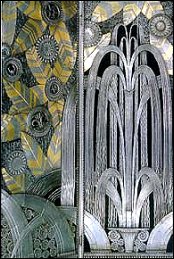

Chrysler building spire

Miami Beach

Miami Beach

Lobby of the Pantages theatre, Los Angeles

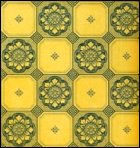

Ceramic charger - Emaux de Longwy

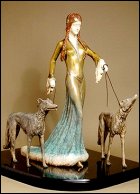

Chryselephantine sculpture by Otto Poertzel

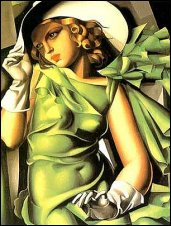

Portrait of Mme Ira Perrot

by Tamara de Lempicka

Perfume ad poster

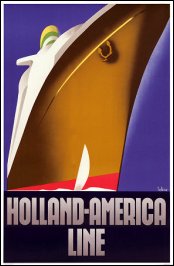

Diningroom of the Normandie

|

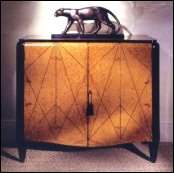

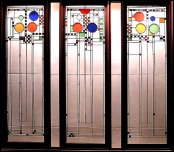

The term Art Deco is applied to the decorative arts as opposed to the fine arts and it was the last truly sumptuous style, sophisticated and decadent. Its influences combined a nostalgia for a romantisized past with the completely modern of the day. Classical Greece, the Middle east & the Orient, Africa, the South Sea Islands & Aztec with the abstraction, distortion & simplification of French Cubism, Russian Constructivism, Italian Futurism, the streamlining of aerodynamics and the machine age and Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. Resulting in the style's recognizable repertoire of motifs, the stylized flower clusters, the female figures, the birds, sphinxes, the running & jumping panthers and the gazelles, the pyramid shapes, the waves, the monumental & muscular male figures, the geometry & the emphasis on speed & power.

It is perceived as the opposite of Art Nouveau, but as a matter of fact, it is in many aspects rather an extension of it, the preoccupation with lavish ornamentation, fine materials and superlative craftsmanship.

The style evolved in France, mainly in Paris, where it manifested itself with exuberance, colour and playfulness. Elsewhere in Europe it was given a more intellectual interpretation based on functionalism & economy, called Art Moderne to distinguish it from the French variant, which was sometimes called high Art Deco. Outside of France ornament was sparingly applied with the exception of architecture in America, where it was adopted to enhance their new buildings, particularly the skyscrapers and the movie palaces.

Modernism emerged during the mid 1920s with its first tenet that form must follow function and it reached its culmination with the formation of the Bauhaus in Germany, which inspired the modernist strain of Art Deco that developed in America in the late 1920s of which the Chrysler building and the Rockefeller Center are good examples.

Nowhere in the United States did Art Deco architecture manifest itself more strongly than in Miami Beach. Following the ruinous hurricanes and flooding of the late 1920s, a new style of architecture appeared, joining the Modernist vision with the fanciful colours & idiosyncrasies of the subtropics.

None of the new buildings exceeds 12 or 13 storeys and most showed a crisply streamlined horizontal line intersected in the centre by a series of strong vertical lines, culminating in a finned tower or cuppola. White stucco alternated with a marvellous range of subtropical pastel facades or trim - pink, green, peach & lavender. The windows were etched with flamingoes, herons, seashells, palms & sunbursts. Neon lighting & flagstaffs completed the effect.

The local cinema provided most of the American population with their only first-hand exposure to the modern style. It was not by accident that in the 1920s cinemas were termed 'movie-palaces'.

Aware that most of the working class eked out a drab livelihood, owners erected glittering theatres where one could retreat into the fantasy world on the silver screen in the most lavish & exotic surroundings available. Extravagance became the keynote & the facade, marquee, entrance vestibule, lobby & auditorium was transformed into a palatial fairyland.

Art Deco used bright colours like orange & red in its interior decoration & combined it with buff, sage, pale green, dusty pink, marine blue, gold, silver & black & white. The rugs were in brilliant fauve colours with cubist designs & jazz motifs. The filmy silks, satin, real or fake fur contrasted dramatically with the gleam of polished wood , lacquer & steel.

Mirrors were perfect for the Art Deco style - they were hung in panels of contrasting colours & shapes, stepped, rounded, fan-shaped or cut-out. Table & floor lamps were in chromed metal, frosted or opal glass, in pink, cream or green with the geometric crescents, sunbursts & zigzag decorations and the wall mounted lamps had fan or shell shaped light-fittings. René Lalique used the simple concept of the suspended basin as point of departure for his ceiling lights. Jean Perzel's originality, precision & technical mastery resulted in the dramatic interplay of superimposed glass disks, hemispheres, cylinders & semi-cylinders, sprayed in soft beige & rose enamel to produce light in a "happy colour that makes women look pretty", seeking to diffuse the light while Boris Lacroix sought to give it solidity, to create a block of radiance.

The sunburst, ziggurat & chevron motifs migrated to furniture & interior decoration & the organic lines of Art Nouveau were replaced by a geometric & stylized opulence, enhanced by the lavish material used. Exotic woods with distinctive grains like burl maple, often veneered in patterns or gilded & silvered, sharkskin, snakeskin, lacquer, ivory, mother-of-pearl, combined with modern materials like chromed steel, aluminium, bakelite & engraved & etched glass.

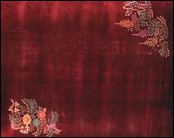

The textile arts are usually ancillary to the major movements in furniture & interior design & due to the ephemeral nature of textiles & wallpaper [with the exception of carpets] it was easy for manufacturers to adopt the latest fad or fashion & the taste for pattern & colour changed more rapidly in this filed than any other.

Electric colours dominated in the early 1920s, vivid shades of lavender, orange-red & hot pink were juxtaposed with lime-greens & chrome yellows to generate a psychedelic palette. The late 1920s ushered in more neutral colour schemes with the emphasis on texture - charcoal, bottle green, dusty brown. The familiar motifs from the Near East, the Orient, folk art, cubism & fauvism were applied with great vigour to textiles, resulting mostly in floral & geometric patterns. Tapestries & rugs were often made to designs created by artists like Henri Matisse, George Rouault, Fernand Léger & Pablo Picasso. In Germany the Bauhaus revived the textile industry & demonstrated an affinity for colour reminiscent of the work of Paul Klee, whose teaching at the workshops helped to free the Bauhaus artists from the conventions of textile pattern & ornament.

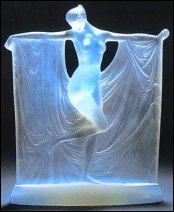

The decorative & sculptural as well as the functional Art Deco glass work had heavy, thick walls, deeply etched or internal decoration like air bubbles & smoky tints, streaks & whorls of mottled & marbled, muted colour. Deeply acid cut abstract & geometric designs contrasted with the polished & raised areas. Transparent glass was decorated in abstract geometric designs with bright enamels painted on both the outside & inside surfaces, elaborately detailed & brilliantly coloured, gilded, mirrored & sandblasted matte to contrast with the polished areas.

René Lalique, famous for his glass work, started as a jewellery designer and his first glass work was his exquisite and innovative perfume bottles. He soon expanded his repertoire to sculptural forms & figurines, lighting, candelabra, car bonnet mascots, vases, wineglasses, chandeliers, tableware, clocks and a glass fountain for the 1925 Paris Exposition. His glass work achieved its exceptionally high relief by blowing or casting the glass into moulds, the glass left clear or in jewel-like colours created with metallic oxides - ruby red, emerald green, sometimes simulating the effect of aging by exposing the glass to metallic oxide fumes. While his themes included naturalistic or stylized animals, flowers, human & mythical forms & abstract geometric patterns, his favourite was the female nude. Other Art Deco glass work included painted & leaded glass windows with the Art Deco motifs, pâte-de-verre, glass engraved to look like bass-relief sculpture, overlaying transparent glass with transparent coloured layers, cut with repeating geometric patterns, cased rose & alabaster glassware, wired glass for internal architectural partitioning & glass bricks to seperate interior spaces & diffuse daylight. In furniture it was used for table tops, shelves & textured glass panels.

Nowhere was the awareness of Orientalism more pronounced than in the Art Deco ceramics, in both the densely decorated & brilliant colours of chinoiserie, often reminiscent of cloisonne enamel work and the simple, monochromatic Japanesque pieces with their subtle, earthy colours, sometimes merged into elegant, monochromatic pieces in rich colours. A variety of Art Deco motifs - the neo-classical, the jazz & abstract geometrical, in black & vivid metallic glazes, most prominently, orange, amber, red & forest green.

Chryselephantine sculptures, gold and ivory statues, often embellished with precious & semi-precious stone, were originally produced by the ancient Greeks and became synonymous with Art Deco.The Art Deco sculptors added silvered & cold-painted bronze to the sumptuous statues of cat-suited chorus girls, flappers dancing the Charleston, acrobatic circus performers, archers, graceful & muscular horses, panthers & gazelles and placed them on elaborate bases of marble, polished granite, onyx & amber.